About an hour outside of Prague, alone among thick forest, swamps, and mountains, there sits a 13th-century castle atop a sheer limestone cliff. The castle Houska (Hoe-skuh) has no outward-facing fortifications, and is guarded only by a lone statue of the saint Ludmila, now weathered and half-covered with moss. Houska cannot be reached by bus, and is too remote to bike to. The only way in is by car.

Though the years have added new structures and purpose to Houska, its original, deeply odd shape remains. It must have taken an enormous amount of time and resources to erect that original structure, but when it was finished, there was little in it that made sense, and even less to encourage human habitation. Houska was not positioned along any trade route, political line, or militarily strategic position. There was no water nearby. There was no kitchen. Some even claim that many of its windows were fake–stone frames that looked pretty from the outside, but let no light within.

Most strangely of all, the castle had no fortifications of any kind. At least–it’s fortifications were not facing the outside. All instead turned within, aimed toward a chapel built over layers upon layers of heavy stone slabs.

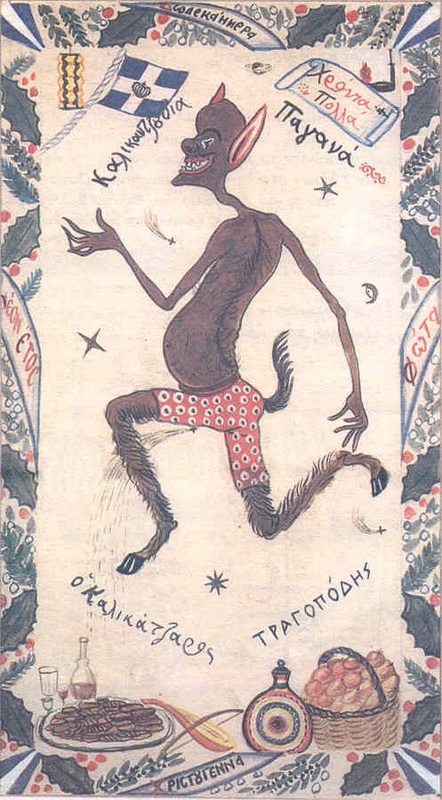

The walls of the chapel are thick. Unusual frescos stretch along them: Saint Michael the Archangel skewers a horned demon. A left-handed centaur aims her arrow at another woman’s throat. As the sun lowers down over the mountains, light disappearing off the altar, screams can be heard echoing from under the rock.

Pit of despair

One of the great things about Houska is how far back its story goes. It could well be that humans inhabited (or avoided) its site since pre-recorded history. The stories that we can corroborate begin around AD 900, when a Slavic prince built a wooden castle there in honor of his beloved son. No sooner did people start to move in did a great crack split underneath of it, releasing unspeakable horrors that quickly left the castle abandoned and the surrounding countryside in terror.

For 300 years, giant creatures with leathery wings stalked the sky, picking off livestock and travelers that got too close to the hole. Half-human, half-beast hybrids attacked people in the woods. Crops wilted and died. Any effort to investigate or seal off the hole was met with frustration at best. It was so deep that none could see its bottom; though the villagers tried to fill it with rocks, it simply swallowed them whole.

Come the mid-1200’s, one Duke Ottokar decided that something had to be done. The Duke set up a little experiment: prisoners condemned to death would be released from their sentence if they would agree to be lowered into this pit and report back on what was down there. The first man to go was a young, eager fellow. He held tight to his rope while the crowd watched the shadows of the pit swallow him. The rope went a little further down, then a little further. Then the screaming began.

The man’s howls echoed in the hole, his rope trembling in the hands of the men desperately pulling him back up. By the time he reached the surface, it was too late. The man’s hair had gone completely white, skin withered and gray, eyes wild, speech hysterical and rambling. He blubbered about a terrible smell, screams in the dark, and then lapsed into incoherence. A few days later, he would die without offering the frightened people any more information.

Some say that the Duke repeated experiment a few more times after that, with similar results. Others say that after seeing what happened to the first guy, no other prisoner volunteered for the job. Either way, if it wasn’t obvious before, it was now: The pit was clearly a gateway to Hell. It had to be covered up.

Down the rabbit hole

The Duke set his men about the long and expensive task of saving the countryside. First the pit was covered with tons of heavy slabs. Then they built a chapel on top of that, with the hope that its symbolism and power would keep the demons permanently at bay. Around that chapel they erected a castle, all of its fortifications built inside out: it was not meant to keep invaders out, after all, but in.

It was a great effort, but not entirely a success. To this day, disturbing visions plague Houska’s surrounding hillside: A horse (or man) runs full speed, their headless stump of a neck gushing blood. A woman in white peeks out of the castle walls. A group of shackled men shuffle forward, carrying dismembered body parts and cringing against attacks from a great black dog. 19th-century poet Karel Hynek Mácha spent the night and not only saw a disturbing funeral procession, but also had a prophetic dream of the year 2006. It’s not exactly a walk in the park.

Add to that the strange, sometimes evil things that keep happening there. Houska has been used variously as a hunting lodge (it is filled with an insane number of deer heads), a dumping ground, and a sanitorium. During the ugly Thirty Years’ War, a sadistic Swedish officer named Oronto took up residence in the castle, hoping that its power would boost his black magic. In a last, desperate effort to stop him, a party of hunters set out to shoot him down. They finally managed to get him through a window of the castle, but as he died, he called out for his black hen–presumably in an effort to work some spell to keep himself around for a while yet. While he didn’t survive, his spirit did, and haunts the castle still.

Then there were the Nazis. Houska was one of several castles that they holed up in during the war, where they stored thousands of confiscated books. It is said that they might have conducted human experiments within the castle walls. Certainly they would have tried to plumb its depths for knowledge of the occult–one of their increasingly desperate tactics to get any edge they could. We may never know; when the Allies defeated them, they burned all records, leaving only nasty memories (and a set of bikes) behind.

Flip that castle

Has the bright light of modernity made the castle any happier of a place to be? Yes and no.

“Yes” in that there are no longer human experiments conducted there (so far as I know…). The castle is now open to the public and can be visited April through October. There are brightly lit, cheerfully decorated parts of it that would fit in in an episode of Gilmore Girls. These can be rented out for various personal, corporate, and artistic occasions–you can even have your wedding there.

“No” in that weird stuff keeps happening. Car batteries won’t start. A wine glass floated several feet into the air in the middle of a conversation. A couple that was winding down in the hunting lodge one evening heard a loud thump. Alarmed, they turned and were faced with two shadowy figures, which approached and started whispering about killing little girls.

But modern science and historical sleuthing can explain this stuff away, right? The visions could be the result of noxious gas leaking out of the crack in the limestone. The reason that Houska didn’t have the usual human accommodations or strategic positioning could be that it was built simply as an administrative building.

The Astonishing Legends podcast (besides being a great resource for those who want to dig more into Houska in general) explores the gaps where these common explanations don’t quite make sense. Why would Duke Ottokar choose to build an administrative building over a giant hole in the ground? Houska is not situated over a volcano…any noxious gas that the initial crack might have produced should have dissipated over the centuries, right? And what kind of gas would it be, exactly, that would cause everyone to have the same types of visions over the years, that wouldn’t automatically kill anyone who got close enough, and that, instead of making people tired and dull, would make them active and fearful (like the poor sap that was first lowered into the pit)?

My favorite myths are ones that can’t be fully dismissed. Houska is one of them. If nothing else, it is a bottomless pit of mystery, and will hopefully leave us guessing for years to come.

Did you know that “Houska” means “braided bread roll” in Czech? Figure out the significance of that sh*t in the comments below.

IMAGE CRED: A big thank you to Ladislav Boháč for Houska in the hills; Scary Side of Earth for both the chapel and the chandelier; ŠJů (cs:ŠJů) for Ludmila; and ladabar for Houska’s exterior.

You must be logged in to post a comment.